Bad Salt (adversarial Devops)

BadSalt (Adversarial DevOps)

Introduction

BadSalt (Adversarial DevOps) was the title of a presentation I gave at DEF CON 27 as part of the Red Team Village. This blogpost will be a written representation of the research and ideas conveyed in the presentation.

My presentation was recorded and I have been told it will be posted on the DEF CON youtube page with the rest of the DEF CON 27 talks once they come out. Below is a placeholder for the video link. I will update this article with the actual link once the video is made available:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ioBAK7hGZi4

Thank you for all those who attended my session live at the Red Team Village, I really appreciate the support! I hope everyone reading this finds the information within useful.

Presentation Abstract for those interested:

https://github.com/3ndG4me/BadSalt/blob/master/research/BadSalt%2BAbstract.md

Slides, code, pcaps, etc…

This is a link to the Github repo where I maintain the “BadSalt” project. The “BadSalt” project itself will be discussed in this post, but this repo also contains my presentation slides, and research artifacts for those who may be interested in that sort of thing.

https://github.com/3ndG4me/BadSalt

Table of Contents

- What is SaltStack?

- Hacking SaltStack

- Hacking with SaltStack

- Detecting Hackers Abusing SaltStack

- Conclusion

What is SaltStack

Short answer: An open source software suite for desired state and configuration management.

The subtext of this article is “Adversarial DevOps”. What this means is that we are going to be exploring modern “DevOps” tools, and how someone acting as an “adversary” may use them to their advantage. While I will be focusing on “SaltStack” as the tool for this idea in this article, there are many tools that can achieve the same goal. This section is intended to catch everyone up to speed on the concepts of configuration management and desired state, as well as mention some of the tools that can help achieve these concepts. So if you were a bit confused by the “short answer” keep reading, I will break those concepts down below!

For starters, let’s tackle the idea of “configuration management”.

Configuration management is exactly what it sounds like. In the context of “DevOps” it’s about managing configurations of applications and infrastructure to establish a baseline for standards across these environments. This concept actually isn’t “new”, system administrators have been managing configurations for years and years. What has changed is how we are approaching the problem. The latest approach has been with new software tools to help us define things in a consistent, version-able manner that helps us get away from doing this by hand and making configuration errors.

Common tools that you may see today when the topic of “DevOps” or “Configuration Management” arises are:

Below I’ll give an overview of each of these, and expound on why I landed on SaltStack as the platform for demonstration of this “Adversarial DevOps” concept.

Puppet

Puppet is one of the most common tools out there for configuration management. It has some maturity to it, it integrates well, and is honestly seen as an “industry leading” tool in some respects.

Often times when you hear about Puppet you may hear it paired with another tool such as “Puppet and Chef” or “Puppet and Ansible”. This is because Puppet’s original function was to simply do “configuration management”. Puppet would be the place you create and store your configurations, and then something like Chef or Ansible would then execute the automation tasks that are defined by Puppet. Puppet has matured much since then but still its primary purpose is to help you manage the configurations and enforce standards across your environments. It’s a foundational tool that is supposed to provide some solid flexibility and integrations.

Chef

Chef is a very popular contender now a days. When Chef first came on the scene it was more focused on the idea “Continuous Automation” not “Configuration Management”. Chef would be the tool suite that executes the actual system configuration tasks that are defined in Puppet. That said much like Puppet, Chef has matured quite a bit in recent years.

Chef’s original focus on this idea of “Continuous Automation” revolved around the concept of “Infrastructure as Code”, or IaC for short. This basically means you will define your infrastructure in some kind of declarative language structure, usually YAML, JSON, but sometimes, like in the case of Vagrant or Chef, it’s Ruby!

Below is a getting started snippet from their docs at https://docs.chef.io/quick_start.html. This creates a test.txt file in the home directory of the system it’s executed on.

file "#{ENV['HOME']}/test.txt" do

content 'This file was created by Chef Infra!'

end

Before Chef was the automation piece to Puppet’s configuration management. Now Chef also touts its ability to “do it all”. Chef offers an entire suite of “DevOps” tools to manage any thing from infrastructure, to code scanning. It’s very interesting, but the main take away here is that Chef is another major tool doing both configuration management and continuous automation.

Ansible

Ansible is a bit different from the other tools discussed so far. Usually when someone describes Ansible I have always thought “oh, so it’s a big mass ssh tool?”. This is more or less true, but is really over simplifying what Ansible does.

Ansible is often seen as THE tool for infrastructure automation. When coupled with something like Puppet or even manual configuration management it is a powerful tool that will execute those standards at scale. Ansible is a fantastic tool for automating and executing tasks across hundreds of systems. That’s it’s job and it does it well. So while you may be able to simplify it down to “ssh into 100 boxes and run a script” it’s much more than that, and there are few tools built well enough to execute on that concept the way Ansible does. I would compare Puppet + Ansible to be close to what one might achieve with Chef or SaltStack as a singular platform.

That said, as these platforms mature, this information will be dated, and our solutions to these problems will have grown.

SaltStack

That brings us to SaltStack. Like the other tools mentioned, configuration management is the name of the game. However, SaltStack brings an interesting focus to the table, “desired state”. If you pay close attention to the Chef documentation, you may pick up that Chef can do this too, but SaltStack is a platform that I believe has this concept as a core focus.

Desired state is the idea that you have a state that your system should exist in. It should exist in this state at all times, and should never deviate. If it does deviate, it should repair itself and resume acting on that state.

This is a very powerful concept to keep in mind as you continue reading, but the point is that SaltStack does this well.

SaltStack is agent based, which means instead of ssh’ing into boxes and running scripts, or making calls to APIs, SaltStack lives on the host it’s automating. This allows, in my opinion, for better integration with more traditional infrastructure while still getting all the modern benefits of configuration management and desired state.

SaltStack’s whole purpose is configuration management and desired state, it can do everything all the other platforms can do without further dependency on other platforms.

Ultimately all of these platforms will help you accomplish modern DevOps goals. They are all very powerful, and very robust and can help with any of the following points:

- Enforce hardening standards!

- Enforce compliance standards!

- Help create uniformity across environments

- Mitigate weird version issues for dependencies in apps/services

- Prevent software from being installed that shouldn’t be!

- Prevent software from being removed that shouldn’t be!

That said, there’s a reason I picked SaltStack for this talk. Part of it was related to my professional career, but the other part lies in the architecture.

Here is a large depiction of the SaltStack architecture and all of its components:

Source: https://www.saltstack.com/blog/whats-saltstack/

As you can see there is A LOT to SaltStack. Between the architecture around the Reactor and Event Bus, to neat tools and integrations like the Pillar or Cloud. However, for the purpose of this article we only care about the “Master” as a whole from the perspective of the “Wheel” and “File Server”, and the client “Beacons” and “Returners”.

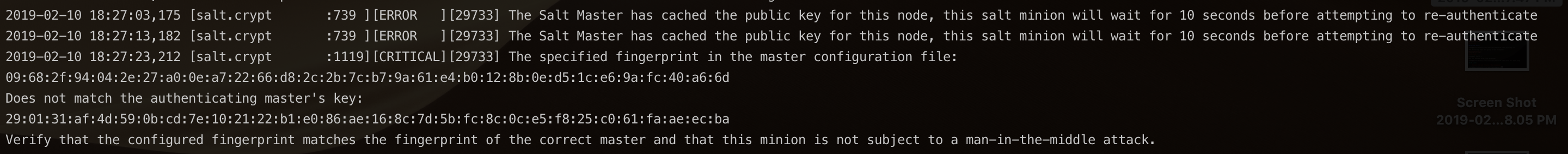

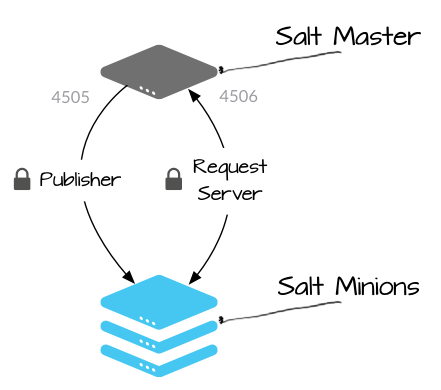

That said there is a much simpler way to look at all of those concepts and that is as the “Salt Master” and “Salt Minion”:

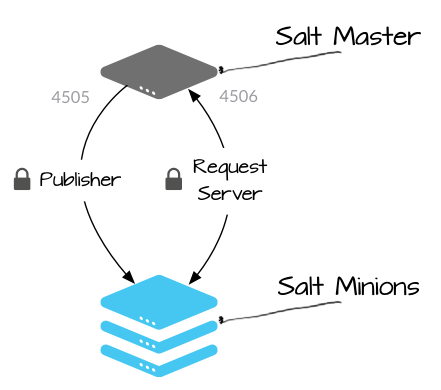

Source: https://docs.saltstack.com/en/getstarted/system/communication.html

Basically, when you set up SaltStack, you establish a server known as the Salt Master. The Salt Master can live anywhere as long as it can listen on port 4505 and 4506, and is accessible by the Salt Minions.

The Salt Minions are the agents. These are Windows Services on Windows and Systemd Services on Linux that you configure to call out to your Salt Master on ports 4505 and 4506 where it will receive and execute instructions, then return their results.

Port 4505: The Publisher service. This service is where commands are posted once you have issued a command on the Master. This can be anything from a simple whoami command to full execution of a desired state. Minions poll this port to uncover what commands they will execute.

Port 4506: The Request Server. This serves two purposes. First, this is where the Minions will return their responses to. So for example, if you execute whoami , the Minion will return root to this service. This is also where the Minion will download any managed files from. If you define a state to put a configuration file in /tmp/config.txt, the Minion will download that file from the Request Server.

So as you can see we have a clear path of command execution, and a clear path of response for that output…sounds kind of like a C2 right?

Keep that in the back of your mind as you read further as well.

For all the reasons listed above, SaltStack seemed like the most desirable candidate to try and abuse from an “adversarial perspective”. So let’s put on our “Red Team” caps and move onto our next topic, Hacking SaltStack.

Hacking SaltStack

For starters, let’s have a quick history lesson.

SaltStack was officially released in November of 2011. While that may not seem very long ago, in 2019, that was 8 years ago. SaltStack is old, and has had some bugs over time.

While SaltStack isn’t very popular, I am certainly not the only researcher who has ever looked into the platform over the last 8 years. At this link you’ll find several CVEs of varying severity dating all the way back to 2013 to as recent as 2018:

https://www.cvedetails.com/vulnerability-list/vendor_id-12943/product_id-26420/Saltstack-Salt.html

The primary goal of what I’ve researched for this concept of “Adversarial DevOps” was not to go find a 0-day in SaltStack. In fact it wasn’t about vulnerability research at all. However, I did want to understand what vulnerabilities might exist for the platform as a potential avenue that I might take in assuming control over a valid SaltStack instance, rather than simply bringing my own.

This meant combing through existing vulnerabilities and scouring for proof of concept code that already existed in the wild.

I actually didn’t find much, but what I did find left me with some interesting conclusions and some awareness that I feel should be raised around managing Salt Minion configurations.

For starters I found the “Evil Minions” project on Github: https://github.com/moio/evil-minions

This isn’t really proof of concept for any vulnerability, but was the first thing I stumbled upon during my search and I found it to be interesting.

In short, it’s a tool for load testing Salt Minion host. It spawns several “rogue minions” that go do all kinds of nasty stuff like filling logs, using up system resources, etc…

While it’s not exploiting any particular issue, it might be cool for doing a DoS, or just to play around with in general, so I thought it deserved an honorable mention.

The next thing I found on my search was more along the lines of what I was looking for.

Chicken Salt: https://github.com/dzderic/chicken-salt

Chicken Salt is a tool that exploits an issue in the Salt Master verification system. Basically, it abuses the verification system to achieve an easy “Man in the Middle” (MitM) attack vector against Salt Minions. It works by sniffing the traffic between a legitimate Minion/Master communication, and within that communication it snags the Master’s public key and a verification token. From there it replays that verification token and serves the public key. All that’s left is to MitM the Minions on a network and you’ll be able to easily convince them to talk to you and execute commands on your behalf.

This is pretty neat, however it appears that it was likely patched in v0.17.1, and might be associated with CVE-2013-4436, but it’s honestly really hard to tell if it was reported on at all.

All I know is that I tried it out, and it doesn’t work now ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

However, what I did uncover was that all modern versions of SaltStack are vulnerable to a different MitM attack vector!

Hope you’re on the edge of your seat now, because that was my trick statement to get you excited. I’m not dropping any 0 days, and again, I didn’t do any vulnerability research for this topic, I just happened to stumble upon this neat little issue that can be abused if Minion configurations are not properly set.

This isn’t really a vulnerability per se, and is known by SaltStack in their design and has clear mitigations. It’s actually just an inherent risk with the design and is hard to mitigate past what controls they’ve already implemented.

With that said, while it isn’t “high risk”, it is easy to pull off given the right conditions. This issue is caused by the need to distribute keys upon initial communication between a Master and a Minion.

For starters let’s talk about the key exchange process:

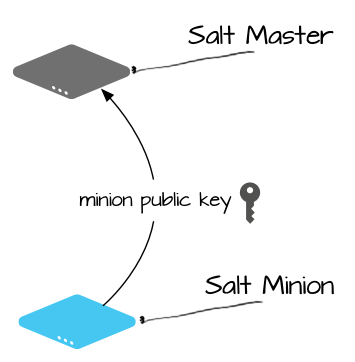

Source: https://docs.saltstack.com/en/getstarted/system/communication.html

As shown in the figure above, on initial communication with Master, a Salt Minion will offer up its public key. All communications between Masters and Minions are done via asymmetric cryptography. The Minion hands over its public key, and from then on the Master can use that key to encrypt all communications sent to the Minion. Once the Minion key is accepted the Salt Master will send the Minion its public key as well which closes the loop to establish the secure communication channel.

So what’s the problem here?

Well, the problem is that a Minion will trust ANY Master on initial communication, even the wrong one.

The solution?

Give the Salt Minions a cryptographic fingerprint from the legitimate Master so that way if they talk to the wrong one, they can refuse communications if the fingerprint doesn’t match.

So cool we’ve solved the problem, everything is good to go right?

Well no…we’ve just added another layer, we still need to answer the question of how the Salt Minion gets the fingerprint in the first place.

The only solution to this problem is to manually issue the Master Fingerprint to Minions on initial deployment. Each Minion comes with its own configuration file with a section to place the fingerprint into. Before you start the Minion service, you must paste in the fingerprint from your legitimate master to the Minion’s configuration. This is the only way to prevent this issue 100% otherwise, a Minion will trust whatever Master it communicates with when it first turns on.

This means if we MitM a Minion during it’s first communications and convince it to talk to an illegitimate Master, then we can take over the Minion with our MitM attack as it will trust any Master by default.

Demo:

What’s going on here is the following:

- We MitM a Salt Minion with bettercap. We are running two instances to facilitate emulating both ports 4505 and 4506 and tunneling them to our own Salt Master that is running on the same host.

- We show that the Salt Minion is configured to talk to the correct Salt Master and start the service.

- We show that the correct Salt Master received no communications from the Salt Minion.

- We show that the “bad” Salt Master successfully received the MitM communications and was able to fully intercept the Minion key exchange resulting in a full Minion take over as long as the Minion continues to talk to our “bad” Salt Master.

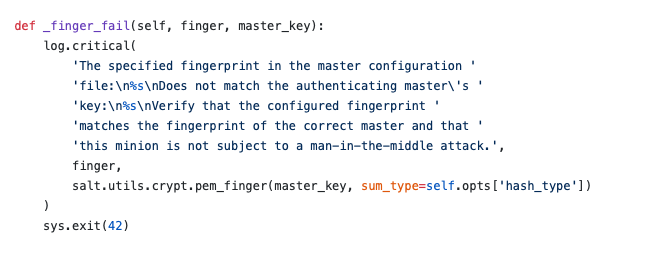

The good news is that this only works on initial communication. Once a Salt Minion has associated with a Master it will store that Master’s fingerprint and use that for validation around whether or not it is talking to the correct Salt Master. If it is not it will actually log this warning to the Salt Minion logs:

Detecting these modern MitM attacks is as simple as reviewing the logs. Unfortunately, if it’s already happened it will be hard to tell based on messages alone. You will have to pay closer attention to exactly what the Minion is communicating to and even check its configuration. Which honestly isn’t difficult, but it’s not as simple as the service just telling you it’s being attacked.

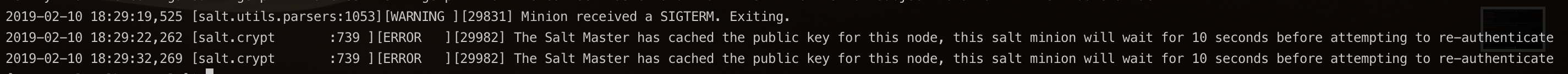

Log after successful attack:

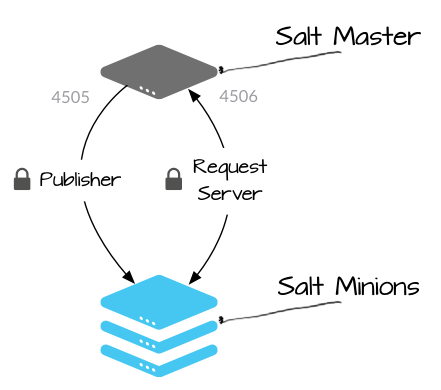

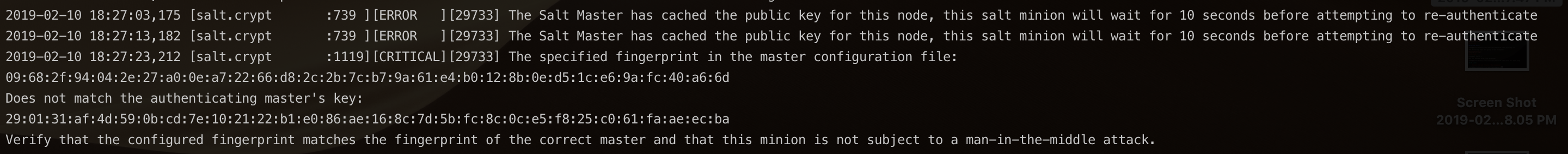

Log after failed attack:

There are only two ways to prevent this modern MitM attack, and they’ve both been touched on above, but we will plainly list them out below:

- Deploy Salt Minions with Master fingerprints defined in their configuration.

- This is the absolute best and most correct solution and there is no reason not to do this. You might as well not even read option 2, because this is the correct solution.

- Immediately accept all incoming connections and hope your minion never deletes its known fingerprint.

- This solution is just OKAY. This only works because the Minion stores the correct fingerprint after initial communications, but that fingerprint isn’t statically defined in the Minion configuration. This means if it’s ever removed for any reason, the Minion could become vulnerable again. Option 2 also doesn’t work if the attacker is already on your network MitM all the things ;)

Overall though, pulling this off requires successfully checking the boxes for a pretty tight attack vector. You would need to:

- Need access to target environment.

- Relatively easy right? We hack systems all the time as offensive security pros.

- Need to be able to MitM on that environment’s network.

- A bit harder, could be network based mitigations in place, but still not too tough in the right conditions.

- Need to catch your target in the middle of a minion deployment

- Here is the niche condition. You need to somehow catch their IT Ops team in the middle of some kind of Minion deployment. Remember this attacker vector only works on Minions that are freshly configured with no fingerprint and have never connected to a Salt Master before. While the lack of having a fingerprint might be the default configuration, catching all of these things at once is a more complex attack vector.

All that said, this is still a very valid attack vector that would often result in root/system access on one or more targets. If you find yourself in the right conditions it might be worth pulling off.

Hacking with SaltStack

Now let’s get into the core of what this research is about. We want to take SaltStack and use it as a tool for adversarially focused operations.

Remember the simplified architecture from earlier?

In its most basic form SaltStack allows us to distribute “agents” AKA “Minions” to our targets, phone home to a Salt Master, and from there we can literally just execute commands from the Master using the cmd.run syntax.

This is as blatant as C2 operations get, but there are lot’s of C2 tools out there. Stuff like Merlin, Empire, Metasploit, etc…

What is the point of using SaltStack as a C2?

It’s important to remember that SaltStack is focused around configuration management and desired state, not C2 operations. So while it does do C2 very well, that’s not what it is built for. Before we dive into that, I wanted to baseline how SaltStack compared as a C2 to other common C2 tools I’ve used on offensive security engagements.

The design where Minions periodically poll the Master for commands resembled Merlin or Empire to me, and since I have been using Merlin a lot more lately, I decided to use that as a baseline to compare and contrast C2 functionality between the two tools.

Starting with Merlin:

Merlin Features:

- Command & Control - Execute system commands and receive their output

- Traffic looks like HTTPS over the http.2 protocol - Allows for lower noise on egress, looks like “normal” web traffic and provides an encrypted channel.

- Post exploitation modules built in - Lets us run scripts like PowerUp or Mimikatz to perform post-exploitation operations for persistence or lateral movement

- Some AV Evastion - This isn’t a touted feature because it won’t always be true, but Merlin is newer and is written in golang. This means it usually won’t be detected by AV because the majority of modern AV softwares have trouble detecting non-signature based golang “malcode”, so at least for now at the time of this article, Merlin is pretty reliable when it comes to bypassing AV. Again, this won’t always be true, but demonstrates a key reason to stay up to date on new tools, languages, and frameworks as an offensive security professional.

How does that “stack” up to SaltStack?:

SaltStack Features:

- Command & Control - Execute system commands and receive their output. Example:

salt '*' cmd.run "whoami"returnsroot - While traffic is pretty unique, SaltStack does provide a secure channel with standard asymmetric cryptography using AES. You can also modify what ports the Salt Master listens on to get better success for Minions being able to get egress traffic out of an environment to the Master.

- Post exploitation modules - We call that desired state! While it’s not built in there is a lot of room for powerful post exploitation automation. Take the concept of desired state, and consider what an attacker would want the system to look like. This is the power in using SaltStack from an adversarial perspective.

- AV Evasion - While you may want to compile your own Salt Minions to reduce your noise footprint, using the default Minion comes with a perk of being trusted software. This means you won’t trigger AV 100% of the time based on the Minion.

Okay so we can kind of see there are some pros and cons in using a purpose built C2 vs SaltStack, but one of the pros I want to focus on is the configuration management and desired state.

Remember that desired state is this concept of forcing a system to configure itself a certain way, and then NEVER deviate from that. Think of this like an adversary:

- Automate deployment of backdoor software

- Automate backdoor accounts

- Automate the deployment of other C2 binaries

- Automate weak security configurations/firewall rules

Then you apply those states on your targets and configure Salt to enforce those states at all times. So if someone ever removes your backdoor, it’ll put itself back. If someone ever deletes the accounts you set up or corrects the firewall rules, Salt will put them right back. This is your box now, you make it look and behave how you want, and if you’re the attacker that can mean all sorts of crazy stuff!

Now granted, you could always do this type of thing. It’s just the idea of persistence automation. That said, SaltStack is made for automation like this, and that’s the whole point. We are looking at how someone with an adversarial mindset might take these new “DevOps” tools and use them for their own purposes. After all, a tool built for the job is often easier to use than something we may cobble to together on our own.

That’s where we get into “BadSalt”.

There is a lot to learn when it comes to SaltStack. Setup can be tedious, and if this is your first time looking into any of this there is a lot to catch up on. You should definitely check out the SaltStack docs, they’re great, but if you just want to dive in and start researching yourself, that’s where BadSalt comes into play.

BadSalt is this little project I’ve cobbled together. Currently it’s basically a bunch of bash and batch scripts that assist with the automation of configuring Salt Masters and Minions for the purpose of use from an offensive security perspective. I originally built this project to assist in automating my research as I was always spinning up new Masters and Minions to test on.

However, I have some further plans to pre-build in some nasty Salt states that are made for post-exploitation. I have already started with a few just to proof of concept the idea, and plan to expound further. I also want to build some kind of stager generator to get into easier deployment of Minions to targets, and even look at building a custom repo to make the whole platform a bit quieter. As you’ll see in our next section, if you use any of this out of the box, and the Blue Team knows what to look for, it’s easy to detect if this tool has been used maliciously.

The project is open source, so if this interest you and you would like to contribute feel free!

Here is a demo of BadSalt in action:

In this video we show that:

- Malwarebytes full is enabled, we are able to download our Salt Minion with a simple batch script from our BadSalt stagers and execute it on the target with no detection by AV.

- It calls home to our Salt Master, we accept the keys.

- We execute a desired state on the target to setup a user called “backdoor” with Administrator and Remote Desktop privileges.

In the BadSalt repo you can take a look at the current proof of concept states. There is one for a backdoor user on both Linux and Windows (Windows one shown in the above demo video), and another state for managing the file deployment of an executable on both Linux and Windows.

The managed file state is labeled with verbiage about meterpreter because I was testing meterpreter hand-offs, but that is the baseline for deployment and execution for any binary or script.

You can find them here: https://github.com/3ndG4me/BadSalt/tree/master/post-exploitation

These states are simply YAML files that declare how the system should look, and make it so. I highly advise checking out the SaltStack docs before you get started as it is important to learn where to store these state configurations and managed files before you get started.

SaltStack Docs: https://docs.saltstack.com/en/latest/contents.html

That said, if you just want to get started with basic C2 communications using BadSalt, all you have to do is replace the network configuration pieces with your own, and run the scripts, should mostly work out of the box.

Detecting Hackers Abusing SaltStack

No Offensive Security Professional is worth their salt if we aren’t building our defenders to be better. Honestly, in my opinion, there’s no such thing as a “Red Team” it’s just a designation for who is doing the super cool offensive security type stuff. In an organization a real “Red Team” is just as much “Blue Team” as the Blue Team is, because after each and every engagement they should be syncing up with the defenders to relay findings and help them prevent those tactics from being used again. This means implementing new detections, helping patch code, educating on better standards and practices. Those all seem like “Blue Team” tasks to me, so if you’re really doing offensive security correctly in general, it should be an extension of our defensive measures, not a separate force. Don’t get me wrong, it’s fun to hack things, but from a professional perspective we have to understand where our value lies, and we can’t just hack in, drop a report, and leave. That makes us almost no better than the criminals in some ways, especially if the issues we find don’t get fixed.

Off my soap box now, I’ll put my money where my mouth is. These are all the ways I found that a defender could detect an attacker abusing SaltStack as an adversarial tool.

First and foremost…Log Analysis!

On *nix systems SaltStack logs can be found in:

- /var/log/master

- /var/log/minion

These logs will have everything you need regarding who, what, when, and where anytime Master/Minion communications occur.

Remember those MitM attack logs?

Those are the Salt Minion logs, and are a great example of how simple log analysis can go a long way in detecting if someone is attacking your SaltStack infrastructure:

Another thing we can do is observe network traffic patterns. SaltSatck communications are fairly unique and easy to identify.

If you’d like to observe some packet capture samples I’ve already done the work and you can find some here:

https://github.com/3ndG4me/BadSalt/tree/master/research/packet_captures

You may notice that port 4505 is mapped to 80 and port 4506 is mapped to 443. This is from testing configuration changes for egress to look like standard web ports. This is the default for BadSalt’s Salt Master configuration and can be changed in its configuration file.

What we should take notice of though is the following pattern.

When a minion calls home:

- Minion -> 80, Master Publishes, “<nothing>”

- Minion -> 443 “Hey want to trust me? ;)”

- If you accept…

- Minion -> 443 “Hey here’s my keys!”

From here we are ready to execute a command, and that looks like the following.

Executing a command:

- salt ‘*’ cmd.run “whoami”

- Minion -> 80, Master Publishes “run whoami”

- Minion -> 443 “root”

Do you see the pattern?

Basically Minions communicate to Masters on an interval of one connection to port 80 followed by one or more connections to port 443. That repeats over and over again and is visualized by previously mentioned communications diagram:

It’s even easier to detect if the default SaltStack ports, 4505 and 4506, are in use.

I’ve also mentioned several times that current installation is very noisy. The following are artifacts you can use to determine if SaltStack has been installed on a system at all:

Existence of SaltStack configuration directories

- /var/log/salt - logs

- /etc/salt - main salt install

- /srv/salt - top files and configurations (master only)

- C:\salt - windows for both

Also check your repo file in *nix or your network logs for communications to repo.saltstack.com as that is where Minions will be fetched from by default.

Also check for the existence of service logs for both Windows and Systemd:

- salt-minion

- salt-master

A final key thing to discuss on the defensive side is detecting multiple minions. If you are an organization that is actually using SaltStack in their environment, an attacker can see that once they’ve compromised a system with a Minion on it. From there they can actually leverage your existing Minion installation to deploy a second Minion service to call back to their Master. This lets them evade all the other initial detections and forensic evidence, but they aren’t home free yet!

To detect a second minion installation look for the following artifacts:

- Check your own logs salt-minion logs (might be shared if the attacker didn’t point to a different log file, or their log file might be sitting in the same directory)

- Check systemd logs for a second salt-minion process

- Could be named anything, but should be spitting out similar service logs for you to compare to

- Network traffic! While you may not be able to alert on that pattern with a wildcard attitude, you could whitelist your Master to detect rogue Masters, or worst case, manually look for communications with a different master.

Obviously, this is an open source platform, and my next goal as an offensive security researcher is going to be writing code to evade as many of these detection mechanisms as possible. That’s how iron sharpens iron in this case though, so it’ll be a fun exercise that we should always be trying to make our security posture even better when it comes to any technologies!

Conclusion

To wrap up, I highly recommend SaltStack as a platform, but honestly any of the tools mentioned are going to be great if you are looking into solving the problems that configuration management and desired state can help you tackle. I highly recommend approaching one of these tools whether you’re in Ops, Defense, or Offense to use to your advantage as they can really help solve many of the system maintenance and management challenges many of us face in the professional field.

A few appreciation shoutouts to the following individuals in my life. I wouldn’t have been able to present this at DEF CON 27 Red Team Village without their support or influence:

- Seth Centerbar - The only reason I chased this research down

- Chris Lamberson - Had my back, listened to me drone on, helped me practice

- Robert King - Constantly supporting my shenanigans

- Daniel Roberson - Shooting the shit whenever

- Dan Borges - First PvJ Captain and ghost mentor (whether he knows it or not!)

- Camilla Parker - Love you!

References:

A lot of this stuff is brand new so I relied HEAVILY on SaltStack’s documentation and the README’s in the Github projects I found. Seth’s brain is probably the key resource here as he and I dove into SaltStack in our day to day at work and he led the charge that inspired me to chase this down outside of work, and helped me learn the platform as quickly as he did.

- Seth’s brain

- https://www.ansible.com/

- https://puppet.com/

- https://www.chef.io/

- https://docs.saltstack.com/en/getstarted/system/communication.html

- https://docs.saltstack.com/en/latest/topics/releases/2014.1.3.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salt_(software)

- https://github.com/dzderic/chicken-salt

- https://github.com/moio/evil-minions

- NVD, MITRE, etc…